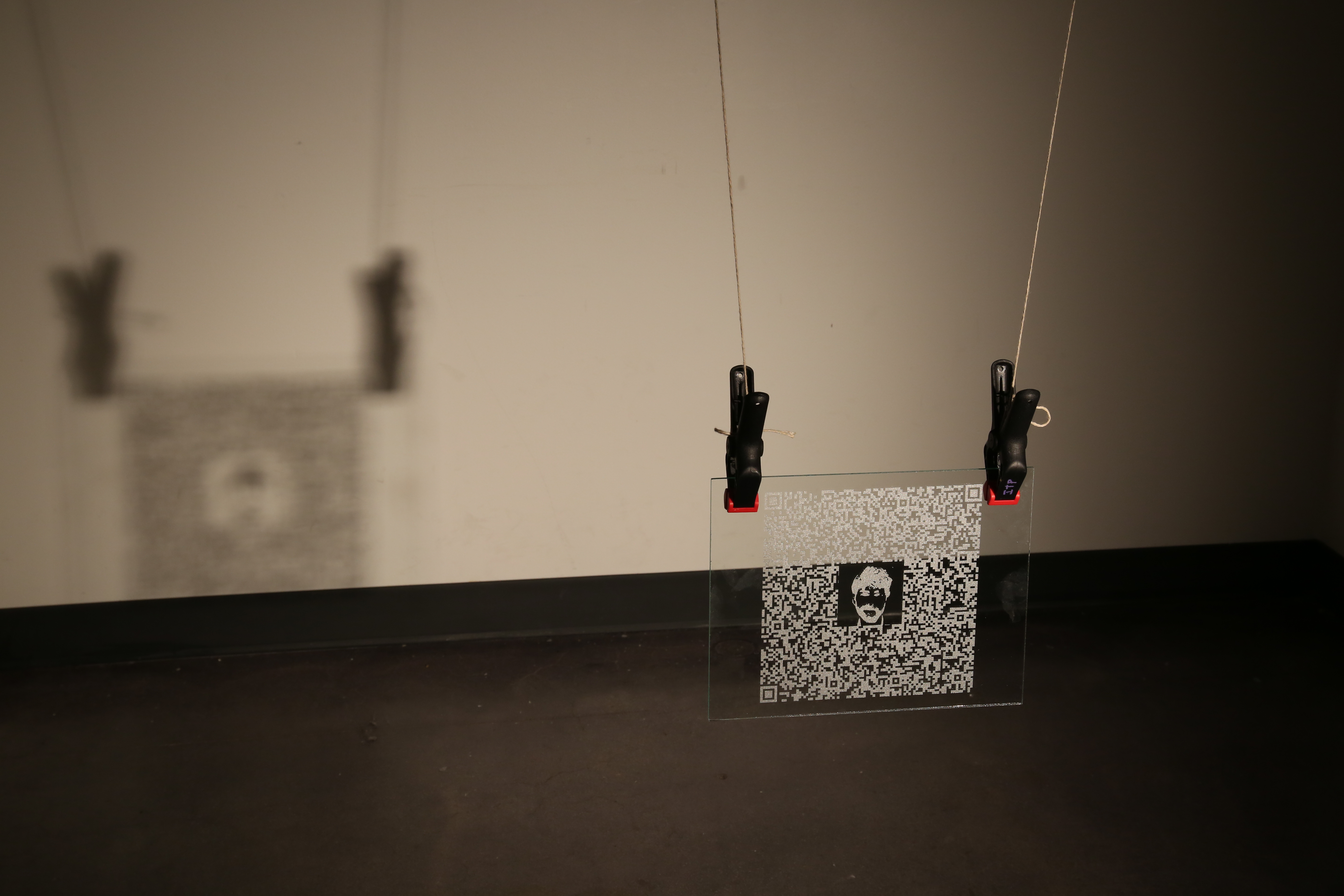

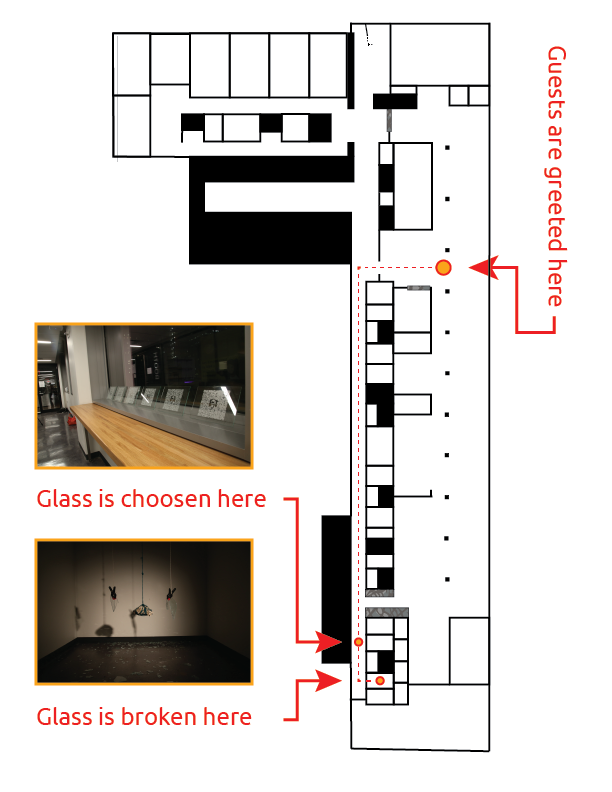

An intimate installation where a few audience members are confronted a choice. Noah Pivnick and I encrypted a deeply shameful or precious secret in a 8.5”x11” glass plate. Then, our guests were guided to a room where they had the possibility of destroying their selected plate, or keep it with them. Anything they choose was possible as long as the glass did not stayed with us.

The sound of glass shattering is visceral and startling. It evokes disquieting associations: the tragic loss of a family heirloom; being menaced with the jagged end of a broken bottle; a rock thrown in hate through a storefront window; the chilling sound of home invasion. It also signifies tension and danger, followed by the shout that stops you at the kitchen threshold: “Don’t come in here! There’s broken glass!”

Glass is a material rich with symbolic meaning. The symbolism of shattered glass is perhaps most powerfully evoked by Kristallnacht, The Night of Broken Glass, during which the Nazis perpetrated systematic attacks on Jewish people and property.

We also drew inspiration from the idiom “people who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones”. The admonition to refrain from judging others lest we be judged ourselves draws a correlation between the materiality of glass (transparent frangible barriers separating inside from outside, self from other, private from public) and flaws in human nature.

And finally, this piece is about memory. Glass has a long history as an information storage medium. Prior to the advent of cellulose nitrate film, photographic emulsions were captured on glass plate negatives. Modern laptop hard drive platters are made from glass. Silicon, one of the elemental building blocks of silicate glass, is the substrate on which the ubiquitous microchip is fabricated.

Memories, like the little cubes of tempered safety glass, are but fragments of a former whole. A point of no return is as inherent to the material as it is to memory. Once broken, glass cannot be returned to its original state, and memory, be it precious or shameful, cannot actually restore a past event. Some memories are sharp and piercing, others are treasured and framed in glass. Memories must be preserved to keep from losing them, be it in the mind or with physical media, and concealed to keep them private, be it in a locked drawer or with encryption.

But like glass, so too encryption can be broken. This is true now more than ever as raw computational power grows exponentially, cryptanalysis becomes ever more sophisticated, and the companies with whom we trust our data become increasingly ethically questionable. We’re taught it’s foolhardy to share our data (though we do it just the same) and when no longer needed, it’s not enough to erase, we must shred the disks and smash the drives to be sure there’s nothing left to reassemble.

Glass Memories

2019 / Encrypted Installation

Collaboration with Noah Pivnick

Toolkit: SHA-256 Encryption, Laser etching, QR Code.

User Journey